Whenever a Scythian slays his first man he drinks some of his blood. He brings the heads of all those he slays in battle back to the king, and by bringing back a head, he receives a share of whatever plunder has been taken…He flays the head by first cutting in a circle around the ears and then, taking hold of it, shaking off the skin. He then scrapes it out with an ox’s rib and works the skin in his hands until he has softened it, after which he uses it as a handkerchief, which he proudly attaches to the bridle of his horse. And he who displays the most skin handkerchiefs is esteemed as the best man. Many Scythians make cloaks to wear from the skins by stitching the scalps together like shepherds’ coats. —Herodotus: The Histories, Book IV

1

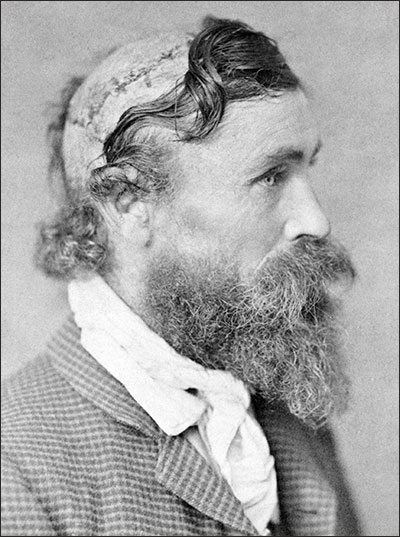

In 1864, Robert McGee, a child, was scalped by Chief Little Turtle.1 McGee lived, and grew up with his head scarred like a baseball. Little Turtle left enough hair at the front of his head that a hat would have covered the bald spot and scars.

Scalping seems a feat more easily accomplished on a dead victim, or with the help of an accomplice. Scalping a live person, even a child, must demand more skill, more strength and coordination. A steadier hand. But then, McGee was probably terrified. An orphaned child of pioneers, he was too young to join the army. Instead, he was hired to drive a wagon along the Santa Fe Trail. Maybe he didn’t even fight, hoping that the tax of his scalp would pay for his life. Maybe he remained perfectly still while Little Turtle held him down in the dirt and cut so slowly, so carefully, like a surgeon, like a woman tracing the outline of her lover’s lips, and Little Turtle tugged and tugged and pulled loose that round disk of skin, that shining tuft of pale hair.

Scalping seems a feat more easily accomplished on a dead victim, or with the help of an accomplice. Scalping a live person, even a child, must demand more skill, more strength and coordination. A steadier hand. But then, McGee was probably terrified. An orphaned child of pioneers, he was too young to join the army. Instead, he was hired to drive a wagon along the Santa Fe Trail. Maybe he didn’t even fight, hoping that the tax of his scalp would pay for his life. Maybe he remained perfectly still while Little Turtle held him down in the dirt and cut so slowly, so carefully, like a surgeon, like a woman tracing the outline of her lover’s lips, and Little Turtle tugged and tugged and pulled loose that round disk of skin, that shining tuft of pale hair.

“Little Turtle.” In English a diminutive name, but in Miami-Illinois it probably named the Midland Painted Turtle, a colorful species that played trickster. Michikinikwa was a war chief of the Miami. Eventually he begged his fellow Indians not to fight white settlers because he did not believe they could win against such weaponry and numbers, but instead of conceding, his people divested him of his title and rode off to be slaughtered at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

Michikinikwa2 traveled up and down the east coast, shaking hands.

2

Herodotus’ Histories3 report on myths, traditions, battles, political pranks, and wonders. In a section on India, he describes a type of ant that is smaller than a dog and larger than a fox and spends its life building anthills of gold. In another section, he tells of a suitor, Hippokleides, who lost the contest for his bride because he danced too wildly—his performance culminated in a headstand on a table, complete with kicks and gesticulations. His antics disgusted the bride’s father. Herodotus questions his sources, sometimes calling a tale “fantastic,” or claiming, “as to who was responsible, I can say no more than I already have.” His narrative is peppered with phrases like “the Spartans say,” and “the Athenians are said to.” There is a degree of honesty in this approach: he admits he doesn’t know much, and that he is often only repeating what he has heard. In the end, he is a teller of tales, hardly to be trusted.

Did the Scythians really drink blood from the skulls of their slain enemies? Did they wear garments made from softened, sewn-together scalps? In my edition of The Histories, a footnote describes skulls found by archeologists that bear evidence of scalping, but Herodotus, writing around 420 BCE, was an embellisher. Scalping is one thing; wiping one’s mouth with a patch of skin is another. Either way, scalping was a horror conducted long before Colombus made his famous mistake. Scalping was neither brought to North America by Europeans nor “invented” by Native Americans. Even the word invented seems wrong. Was slow-slicing—the practice of cutting a victim repeatedly until he bleeds to death—“invented?” Or the attaching of electrical paraphernalia to a prisoner’s genitals? Do we seek to name the “inventor” of scalping as a way to free ourselves of guilt? Or to claim it? (It was us. Blame us. Let us say that we are sorry.)

Who would think to cut a cap of skin as proof of one’s brutality?

In 2 Maccabees, a Catholic and Eastern Orthodox book of the Bible, seven brothers are martyred for refusing to eat pork. They are whipped. Their fingers are cut off. They are burned and bled and dismembered. Their limbs are fried in a pan. The first brother’s torture is described: “When they had pulled off the skin of his head with the hair, they asked him, Wilt thou eat, before thou be punished throughout every member of thy body?”4 But each brother refuses to eat. Each brother is killed for his refusal.

It seems that, for a time, almost anyone in North America scalped. French, English, American, Native American, Mexican. Europeans fighting with each other and with Indians, devised a bounty system for scalps, encouraging the practice. Settlers scalped. Indians scalped. Pastors scalped. Parishioners scalped. During the American Revolutionary War, British officer Henry Hamilton was known to the colonists as the Hair Buyer General because he allegedly paid so generously for the scalps of colonial Americans. And John Lovewell, a well-known scalp hunter, once paraded through the streets of Boston wearing a wig made from the scalps of his Abenaki victims, for which he was paid 1000 pounds.

The Mexican government paid for the scalps of Apaches, identified only by their skin and hair color. Chief Gomez of the Mescaleros began paying for the scalps of Mexicans and Americans in an attempt to balance the market. A band of Kickapoo and Mexican scalp hunters turned on each other, the Mexicans claiming the scalps of the Kickapoo and cashing them in with their government.5

No matter what color scalp one held, there was someone who would pay for it.

3

Heads bleed a lot when they’re cut. And they have so many nerves. What nightmares lace the sleep of the scalped? Robert McGee’s eyelashes look charred.

I could purchase a print of McGee’s scalped profile from Amazon.com for $57.00, a savings of $14.25 over some mysterious market price.6 But where would one hang it? In the living room, above the fireplace? Certainly not in the bedroom. Maybe it would be the first in a collection of prints documenting the violence of one person against another. Or documents of genocide.

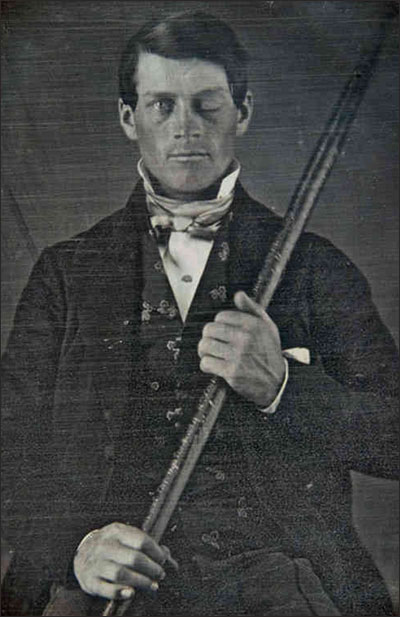

Or McGee’s could be the first in a collection of portraits of the strangely head injured. His profile could hang beside a portrait of Phineas Gage, a nineteenth century railroad foreman who was the victim of accidental lobotomy when an explosion at work sent a tamping iron through his cheek, into his brain, and out the top of his skull.

Or McGee’s could be the first in a collection of portraits of the strangely head injured. His profile could hang beside a portrait of Phineas Gage, a nineteenth century railroad foreman who was the victim of accidental lobotomy when an explosion at work sent a tamping iron through his cheek, into his brain, and out the top of his skull.

The tamping iron flew a good distance from Gage, taking with it some of his brain and some of his blood. Gage lost vision in one eye, but his head healed. He learned to live a fairly normal life, and drove a stagecoach in Chile for years after the accident. But before the accident Gage was known for his efficiency and capability, and afterwards he was unpredictable, capricious, fitful, and profane.7

Next in the collection might hang the X-rays of a contemporary Chinese man’s skull, a four-inch blade lodged within.8

The man, Li Fuyan, claims he was stabbed in a robbery four years before surgeons removed the blade, which they discovered only after the man complained of serious breathing problems and headaches. The blade was corrupted from its time in his skull, lace-edged and rusty. If it had remained there, would the man’s body have continued to work at the blade, nibbling at it like some crashed car at the bottom of a lake, corroding the metal until it was only toothpick-sized and the man had long since stopped consuming painkillers and wheezing? It was an alien nesting between nasal passages. It was exaggerated shrapnel.

The man, Li Fuyan, claims he was stabbed in a robbery four years before surgeons removed the blade, which they discovered only after the man complained of serious breathing problems and headaches. The blade was corrupted from its time in his skull, lace-edged and rusty. If it had remained there, would the man’s body have continued to work at the blade, nibbling at it like some crashed car at the bottom of a lake, corroding the metal until it was only toothpick-sized and the man had long since stopped consuming painkillers and wheezing? It was an alien nesting between nasal passages. It was exaggerated shrapnel.

4

In Massachusetts, 1697, young wife and mother Hannah Dustin was taken from her home by a group of Micmac warriors. As the story goes, they marched her barefoot through the snow in her nightgown until they reached their village, where they left her. Her guards, a family, slept beside her, but Dustin stayed awake. She killed the sleepers with a tomahawk and escaped downriver in a canoe with two other abductees. But before they left, they hacked holes in the other canoes so they would not be pursued. Before they left, Hannah Dustin removed the scalps of her ten victims.

Back home, she was paid generously for the two adult male scalps. The rest of the scalps belonged to women and children and so they were worth little-to-no money. A sculpture of Hannah Dustin stands on a pedestal in Boscawen, New Hampshire. Her carved hair and nightgown blow behind her. In one hand she holds a tomahawk; in the other, a bouquet of dangling scalps.

5

For many tribes, wearing one’s hair in a scalp-lock was not only a matter of honor, it was expected. As described by Ben Armstrong—a white southerner who moved north, learned the Ojibwe language and culture, and was initiated into the tribe in the 1830s—the Indian scalp-lock was a section of hair about the size of a silver dollar, braided at the center of the scalp. The braid was tied off at about half its length, then wrapped tightly in bark or leather, or later, in red flannel—the top choice wrapping because it was flamboyant. The scalp-lock was a trophy a Sioux or Chippewa man was equally prepared to give or take.9

In contrast, many white settlers cut their hair as closely as possible, an act that made it more difficult to remove their scalps (the lock allowed for leverage and grip when the scalp was yanked off. Apparently its moment of release was accompanied by a flopping sound). Short hair also made their scalps less desirable trophies.

Does the texture of one scalp differ much from the texture of another? This one stretched and rubbed smooth. This one thick-skinned. This one thin. And how did one treat a scalp in order to keep it supple, to use it to dab the corners of one’s mouth? What has happened to all those scalps? The heaps and heaps of scalps that were taken, so many shades of skin, so many colors of hair. Where are they? How long does a scalp last?

6

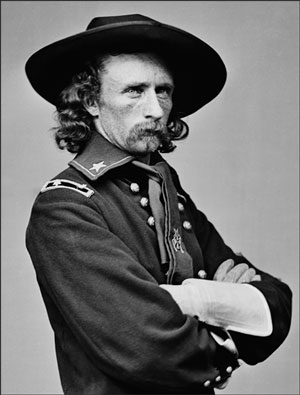

General George Armstrong Custer was known for his long blond ringlets. He often posed with guns, wearing a uniform and tall boots. He was a sloucher with a weasel-like face and a moustache like a small animal crouching on his upper lip. Among other nicknames, he was Hi-es-tzie, Long Hair.

General George Armstrong Custer was known for his long blond ringlets. He often posed with guns, wearing a uniform and tall boots. He was a sloucher with a weasel-like face and a moustache like a small animal crouching on his upper lip. Among other nicknames, he was Hi-es-tzie, Long Hair.

I cannot look at an image of General George Armstrong Custer without imagining bodies strewn across the plains. Four centuries of bodies, brown bodies and white bodies, heaped in ditches and mass graves. Shot. Stabbed. Scalped. Bludgeoned. Is it unfair to see all these in Custer? To try to contain them there?

It is said that Custer polished and smoothed his ringlets with cinnamon scented oil. All that hair hanging around his chinless face. Would I be more compassionate—more haunted—if he were more attractive? Custer reflects my selfishness, my vanity, my desire for a simple equation: for evil to be ugly.

The history of the Battle of Little Bighorn is one Herodotus would have loved, full of contradictory accounts and unanswered questions. Various people claimed to have dealt Custer his final blow, to have fired the shot that pierced his breast or blew out his brains. When his body was found, there were two holes in it: one through his chest and one through his cheek. It is said that the Lakota left his scalp—balding, the blond locks recently trimmed short—intact. That no one wanted that hair—a valuable trophy, but dirtier than it was worth. Bad Medicine, Custer.

Custer died when:10

1. Early in the battle, Joseph White Crow Bull, an Ogallala Sioux, shot a rider who wore buckskin and a large hat. The man shouted orders to the troops, indicating he was an officer. But this remembered shot was fired nearly a mile from the place where Custer’s body was found. (And who remembers where they fired a particular shot during a battle? And many riders wore buckskin and hats. Many riders from both sides were killed by friends and allies in the chaos.)

2. Buffalo Calf Road Woman, who fought with the men, knocked him from his horse. His fall was fatal. Or at least final.11

3. After years of denying responsibility, claiming that there was far too much smoke and dust during the battle for anyone to know who killed Custer, Rain-in-the-Face, an Unkpapa Sioux, confessed on his deathbed: “Yes, I killed him. I was so close to him that the powder from my gun blackened his face.”

4. A Cheyenne named Hawk, who looked similar to Rain-in-the-Face on the day of the battle—both wore yellow body paint, but Hawk carried a larger blue shield—fired the fatal shot.

5. Gravely wounded, his men dead around him, he walked the battlefield alone, then put his own gun to his temple and finished the job.

6. Other.

Custer may have fathered a child with a woman named Me-o-tzi, or Monaseetah, “The young grass that shoots in the spring.” But the father of her child may have been Custer’s brother Tom. It’s rumored that the General may have been sterile after a fierce bout of gonorrhea he acquired while at West Point.

Tom Custer was also killed at the Battle of Little Bighorn, his heart carved out of his chest and paraded around on a stick while the Lakota danced and stomped.

General George Custer may have loved a Cheyenne woman. Or, rather, a Cheyenne woman may have been his lover. But her father, Chief Little Rock, had been killed in a battle with Custer’s men. And because both George and Tom may have slept with Monaseetah after they killed her father, “love” and “lover” don’t seem the right words. Hers was an oral tradition. Things were not written down. Monaseetah, it is said, stayed in her tent. She had a son with a streak of pale hair. She never married. Or she was divorced and notoriously picky. Or, much later, after Custer’s death, she married a white man named Isaac. Her name is everywhere in writing about Custer, but there is little agreement in the stories. Custer wrote a letter to his wife—he wrote so many letters to his wife—in which he described Monaseetah’s silken hair, waist-long and black as a raven.12

It is said that when Custer’s body lay on the battlefield among the dead, two relatives of Monaseetah found him.13 They called him their relative, persuading the man who was prepared to desecrate his body to leave him alone. Then they thrust their sewing awls into his ears that he might hear more clearly in the afterlife. Clear out the wax. Rearrange his brain.

If, in the case of Phineas Gage, an efficient, kind man turned sour, crass, and volatile after his brain was punctured, perhaps Custer’s personality—a whore for the media? A politician? A soldier well acquainted with killing? A murderer?—would turn gentle in the afterlife.

Many reports on the condition of Custer’s corpse agree that he looked peaceful in death. That he was sitting upright between two of his soldiers, almost-a-smile on his lips. That his body was nude but for socks. That it was unmarked and whole. But there are also rumors of his slashed thighs and missing fingers, of arrows through his genitals, and gun smoke that smeared his face. Rumors that those who found him made a pact to spread peaceful falsehoods for the sake of Mrs. Custer. They would say the General’s body had not been touched.

But back in 1876, as her husband rode off to his final battle, Elizabeth “Libby” Custer wrote that she was filled with trepidation.14

Did she dream of her husband’s pale scalp flying from a pole, his long yellow hair streaming like ribbons in the wind?

And in another place, not far away, Sitting Bull had a vision of earless white warriors falling on his camp like a swarm of ugly locusts—greasy, crushable, and overwhelming.15