Teri Frame’s research and studio practices focus on the human body. Although she was trained as a ceramist, performance art, film, and photography have come into her work and she continues to move among these genres. Frame has exhibited, lectured, and taught internationally and throughout the United States. She has completed artist residencies at the Emmanuel College, The MacDowell Colony, PlatteForum, and the Museum of Outdoor Arts.

Pre-human, Post-human, Inhuman is a performance series that employs raw clay masks as a means for altering the human body. It was performed at the 2011 NCECA conference Project Space in the central hall of the Tampa Convention Center. Each performance was subsequently recorded at the Alberta College of Art and Design. The piece addresses changing human bodies in six acts, titled Simians, Early Humans, Hybrids, Proportions, Races, and Post-humans, respectively. It is not a didactic or chronological enactment of the evolution of the human body, but rather an acknowledgement of the ways in which our notions of bodies have migrated throughout time and have been manifested in the arts and sciences.

Act I: Simians explores the boundaries between human and animal. During this act I take on the forms, postures, and gestures of our closest living ancestors, the other great apes, and examine the behaviors and characteristics of bonobo, chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan. By studying what has been designated as inhuman, it is my intent to better understand what is human.

Act II: Early Humans is an uncovering—an excavation of hominid form and the changes that it has undergone throughout the past 3.5 million years. Such changes include varying degrees of upright posture, the transition from power grip to precision grip and its relationship to stone tool technology, and ratios between cranial size and the placement of facial features.

Act III: Hybrids examines the world of human/animal composites. Some of the earliest examples were painted in the caves at Lascaux and sculpted in stone and clay nearly 30,000 years ago. Such creatures have been universally prevalent within mythology, and recent concerns over genetic engineering reveal a timeless preoccupation with the notion of the para-human. The Roman architect Vitruvius admonished the hybrid creatures that were painted in decorative borders at the baths of Titus and Nero’s Domus Aurea for their disorderliness and poor taste. Non-normative bodies have often been shunted from the human realm to that of the animal. Disfigurements in the form and the surface of the human body are marginalized. Those who bear such marks are estranged from public life, and are often animalized. One famous example is that of the late Joseph Merrick, otherwise known as Victorian England’s “Elephant Man.” Merrick was plagued with Proteus disease, a rare affliction accompanied by gigantism of the limbs and various dermatological complications. It distorts the features of those who bear its mark.

Greek corporeal models, which have had a tremendous influence on Western culture, were portrayed in whole-bodied, symmetrical, and blemish-free marble statuary. The rules for bodily proportion were set forth by Polykeitos in the Kanon, and reinforced by Vitruvius in de Architectura. Act IV: Proportions explores a corporeality that diverges from such ideals. During the Enlightenment, pseudo-sciences such as physiognomy and phrenology linked the proportions of the head and face with morality, and condemned non-Europeans for falling outside of the proportional ‘norm.’ The proliferation of genetic engineering and aesthetic surgery reflects how notions of ideal beauty continue to be at the forefront of human preoccupation, in the East and West alike.

Act V: Races scrutinizes the notion of race and the proportional norms and facial characteristics of people from four geographical locations (Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas). Craniometry has been utilized by paleoanthropologists since the 19th century. Forensic anthropologists have often relied upon it, and have developed accompanying tissue tables (records of soft tissue thicknesses associated with various groups of people), in order to determine the races of unidentified human remains through forensic facial reconstruction. These practices, deemed useful in some fields, have also been used to condemn various “races” by linking facial and cranial measurements with morality, similar to physiognomy and phrenology.

Act VI: Post-humans considers how past migrations in the form of the human body might impact its impending physical changes. It has been said that with recent technological advancements, Homo sapiens has become post-human, perhaps cyborg, and that as our bodies merge with new technologies, our humanity becomes diminished. If that is so, then perhaps this change began when Homo erectus first employed technology in the form of sticks and stones.

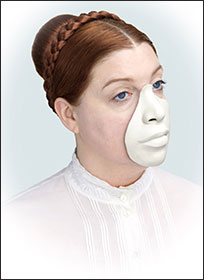

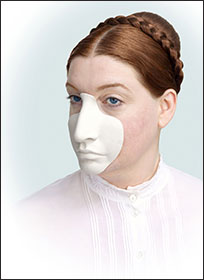

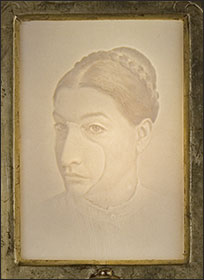

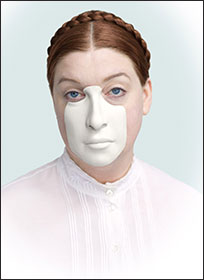

Within these five self-portraits, photographed by Doug DuBois, I don porcelain facial prosthetics modeled after the noses and surrounding areas of pre-operative “ethnic rhinoplasty” patients, which I found on plastic surgery websites. I combine these masks with nineteenth-century colonial dress to examine contemporary beauty paradigms within the United States, and their relationships to the not-so-distant past.

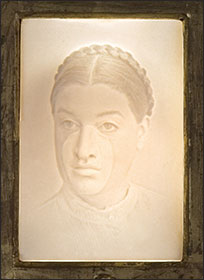

Each of the five images has been translated into a low-relief porcelain photograph (a.k.a. lithophane) via 3D modeling software, and has been mounted in a handled frame. These objects, known as “complexion fans,” were popular during the Victorian era. Affluent women held the fans as they socialized around the fireplace in order to keep their faces from flushing and makeup from melting.